The Value of Unstructured Time (Or: What to Do Instead of TV)

I recently wrote a blog post about the potential harm to young children from excessive screen time. The post led to a lot of online discussion, and I noticed that two comments came up frequently: What would I do to keep my children entertained without a screen? And: What if there is nothing more productive for them to do than use an iPad—wouldn’t it better to have a quality app than boredom and whining?

For some well-meaning, busy parents, screens allow children to pass time without demanding attention, and serve as a helpful way to fill time where parents can’t be 100% focused on their children. Our focus at LePort is primarily on what is best for the child, but we’re always sympathetic to the reality that we as parents also have needs (including down time, opportunities to rejuvenate ourselves, and long lists of practical tasks that must be completed).

There are also families for whom screen time isn’t an issue because the children are simply too busy! They are enrolled in an ambitious number of after-school activities: soccer, dance or gymnastics, choir classes or instrument lessons, art workshops or theater groups, or after-school academic programs, such as preschool Kumon or language classes.

We believe that in both family situations, the children miss out on a centrally important value: unstructured time. To put the point in a deliberately strong way, children need boredom. The self-initiated effort to solve boredom leads to creative thinking. Children benefit from having to find a way to entertain themselves, to just hang out with siblings and friends and make up games, time to play, to build, to draw, time to think and dream.

Why unstructured time is important

A lot has written about the importance of unstructured time; just google "the value of unstructured time for children" to read many articles. A good, rather detailed article is The Play Deficit, by Peter Gray, one of the most fervent advocates of free play learning. (We don’t agree with everything Dr. Gray advocates; as Montessorians, we believe there needs to be more thought given to preparing the environment that children interact in and the ultimate content of what they learn, as against Dr. Gray’s advocacy of unschooling, but we do agree with his assessment of the importance of child-led activity and the need for unstructured time.)

There are many reasons to ensure children have unstructured time, ideally in the company of other children in a mixed-age setting. Here are a few to consider:

- Acquiring a sense of self. Many adults are disappointed at the lack of passion and drive many teenagers and even young adults exhibit. They go to college, yet don’t know what to do with their lives. But how could they, if their "self" never had room to blossom? All too often, adults set the agenda for most of a child’s waking hours, from a tightly-scheduled preschool or school schedule, to adult-led youth sports and after-school enrichment classes. To individualize themselves and find their own identity, children need regular practice in making choices, and unstructured time within the right type of environment offers just this practice.

- Learning to interact with other people and develop social skills. In adult-led settings, whether school or organized after-school activities, children rarely have the opportunity to freely interact with each other. Yet this type of child-to-child interaction, free from adult direction, is exactly what they need to figure out how to make friends, to learn how their behaviors (being bossy, pushing others, sulking) affects others and their ability to play with them. Of course, adults should be there to help the child interpret and process the experience—but the key is that the child actually gets to have the experience of unmoderated (or lightly moderated) interaction. Unstructured time, especially in mixed-age groups of other children, provides an optimal environment for children to try out different behaviors and to learn social interaction through doing.

- Learning self-discipline and building sustained attention. To successfully acquire knowledge today, and to flourish as adults tomorrow, children need to learn to control their impulses, to organize themselves, to manage their time. Learning presupposes the ability to sustain attention, to preserve with a cognitive or physical task until one succeeds. These foundational skills require space and time to practice: there is a huge difference between the Montessori ideal—a second or third grader who makes a weekly work plan, figures out when to do what task, and learns that work doesn’t just go away when ignored, and the ideal traditional school environment, where adults dictate to children in 30 or 45-minute increments what they need to do, when, in which order, and secure smooth transitions to training and prompts. Children need time to really immerse themselves in an activity. They need practice to sustain attention, to tackle large projects. They need space to learn self-discipline and organization skills.

- Effective skill practice. All young mammals play. Why? Because as mammals, the capacity to adapt is inherent in successful living. There are many skills that are not inborn, but need development, whether it’s chasing a mouse or climbing a tree. The same holds true for human children, only significantly more so: because we aren’t dominated by innate instincts of self-preservation, we need to learn every skill we need in life! Children need to learn to control their bodies—to develop balance, to swim, ride a bike, to pour water without spilling, to cut vegetables, to hold a pencil well. They need to practice intellectual skills—from writing to reading, from arithmetic to grammar, from spatial perception to building logical arguments. While preschool play is usually focused more on physical skills, older children often learn many intellectual skills during free play. I recently spoke with a successful engineer who credits his hours of Lego free-play as a child with his tremendous ability to visualize complex three-dimensional structures!

In our Montessori classrooms, we provide children with extended periods of unstructured time for child-led activity within a carefully prepared environment: each day, for about three hours in the morning, and two hours in the afternoon, children can choose what they want to do. They have access to a wide range of Montessori materials, which have been culled based on whether children repeatedly found them enticing and engaging: Dr. Montessori tried many different activities, in scores of schools, across the world, and retained only those that children freely chose to interact with, on a repetitive basis (in addition to serving a specific function in a defined learning sequence). Children can choose to work with any activity they’ve received a brief lesson on; they can work with it alone or with a freely-chosen friend or two; they decide how long they want to use the activity and where they want to take it. The result is the self-initiated acquisition of an important, life-serving body of skills and content.

What children can do during unstructured time at home

If you agree with these arguments on the importance of open-ended, unstructured activities, you can bring them into your child’s life at home, not just at preschool or elementary school. Start by setting a strict limit on TV time (which otherwise can crowd out unstructured, active play), and ensure that your child isn’t over-scheduled with after-school activities (in our family, the limit is two scheduled activities per child per week).

Once you have reclaimed unstructured time, here are some ideas on how to help your child use it actively, without whining about boredom:

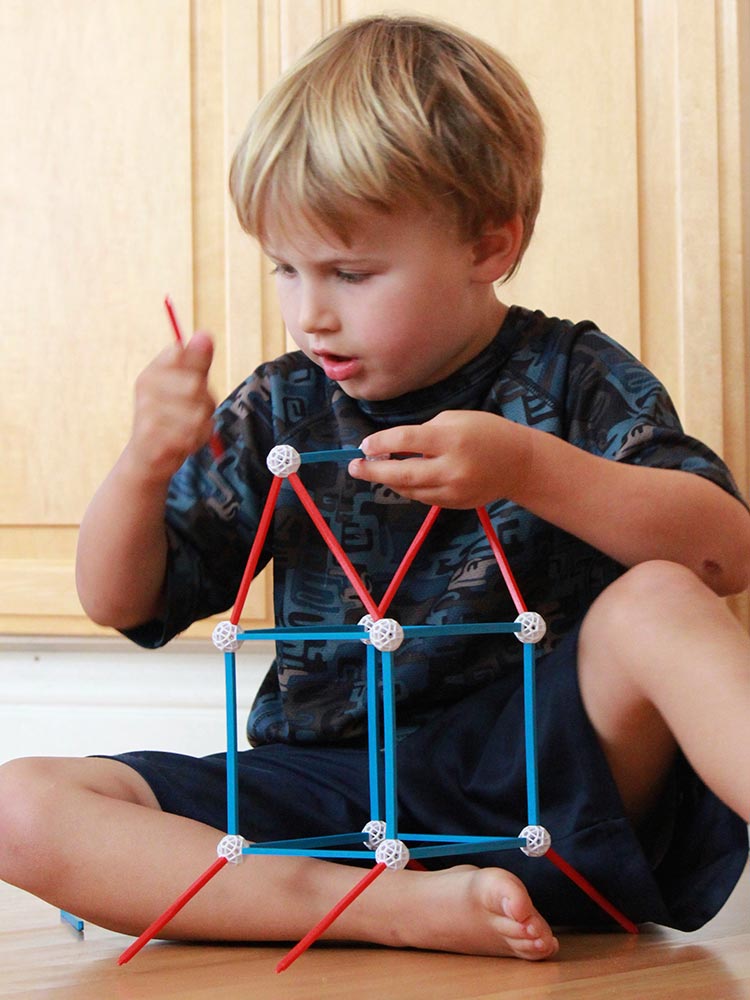

- Provide plenty of unstructured, multi-purpose play materials. The best playthings can be used in many different ways: often, an empty box is all children need (although it helps to also have scissors, paper, string and sticks). Other great items are all kinds of building materials, such as Legos, Citiblocs, Zoobs, Magformers, Zometools, Lincoln Logs and Tinker Toys. At my daughter’s Montessori school, they take building to a different level with Builder Boards, a full-size version of Lincoln Logs that children build elaborate play forts with! A variety of stuffed animals, trains and trucks can also come in handy, as can your permission to repurpose household items, from couch cushions to old sheets, from your clothes for dress-up, to kitchen utensils. The more open-ended, the better: children are much more creative if you buy boxes of Lego parts to freely build with, rather than elaborate sets that need to be built a specific way. (In our house, all but one of these sets has been disassembled and put into the box of bricks, and I’ve given up any effort to keep the pieces of even elaborate, gifted items like a fire truck together.)

- Give access to different types of art materials (not project-specific crafts kits). In her excellent book, Renegade Rules, Heather Shumaker makes a helpful differentiation between arts and crafts: art, for children, is often all about free exploration of different materials—whereas crafts tend to be adult-led projects (the type you often see exhibited on the walls of preschools!). In our Montessori classrooms, children are free to work with a wide range of art materials; the goal is to let them explore creatively, rather than make them complete beautiful projects. Often, art for preschoolers is all about the medium, the process, not the result! You can do the same at home by providing materials without much instruction: Get an easel with a chalk board and roll of paper; buy large-sized sheets of cheap drawing paper; have jars of pencils and crayons easily accessible; show preschoolers how to draw with washable paints and clean up afterwards. Give them access to colored paper, scissors, string, foam, pipe cleaners, beads, Perler beads, play dough or craft clay, and leave them free to create. (You can and should expect them to clean up their own messes; it helps if craft materials are readily accessible, in a clear place in the house, and if the children have access to child-sized buckets, sponges and brooms to clean up their own mess.)

- Get your children outside, ideally together with a gaggle of friends. Lenore Skenazy, author of Free Range Kids, Richard Louv, author of Last Child in the Woods, and many others argue that children today are missing out on the type of childhood baby boomers took for granted—one where your parents sent you outside with the neighborhood children to play until dusk came or until a dinner bell rang. While just sending the children outside has become harder today, it’s still possible to protect free-play time outside. If you have a yard, your preschooler can easily play outside; invite a friend over if he’s bored and has no siblings to play with. Go to a local park at a regular time each week—and soon your child will find playmates to make up games with. Or organize a few parents from your child’s school for unstructured after-school, weekend or summer camp play experiences at local parks. This summer, families at my daughter’s school did this with a group of five- and six-year-old girls, and it was a blast! Not only did the children enjoy it tremendously, it was a great way for the parents to see their children interact with each other freely. I, for one, felt I got to know my daughter better by spending a day observing her interact freely with her little friends.

- Create inviting reading corners and equip them with great picture books. For ideas on how to do this, read our previous blog posts on setting up a prepared environment for reading, and building a great home library.

- Train concentration. If your child has a hard time remaining engaged in an activity without repeated adult intervention, don’t try to do too much at once. Recognize that concentration itself is a learned skill, and look for opportunities to develop that skill. It might require an additional investment of time upfront. You may have to be prepared to be interrupted the first few times your child plays with Legos and experiences the frustration of not having you sit beside him, but if you gradually wean him off your constant attention, he’ll eventually be able to function for long stretches without your active involvement.

As a conscientious parent, it is very easy to get drawn into the maelstrom of an overly-structured schedule: after all, we want the best for our child, and there are so many enticing activities out there! It’s also easy to turn on an iPad or TV when you are busy and a child starts whining. Yet there is so much to gain from protecting unstructured time: isn’t it worth giving it a try?