Purposeful Movement, not Random Activity: The Montessori Contribution

Often, when we talk with parents of two- or three-year old children, especially boys, they express a concern that their child is rambunctious, active, maybe even a little wild or clumsy—and that as such, perhaps they would be out of place in a Montessori classroom. Visiting our schools, they see children intently focused on their activities; they notice the quiet, busy hum in the classroom, they watch little people move about in a very coordinated way, and I can almost read their minds as they think, "My son would stick out like a sore thumb in this class!"

If these parents go on to enroll, they almost invariably discover that their fears were unfounded. Their child too comes to move purposefully, channel his energy towards activities that engage him, and flourish in the Montessori environment. The reason this happens is simple: a Montessori prepared environment is deliberately designed to meet the needs of a developing child, including foremost the need to move purposefully.

A child’s impulse to move is central to his biological development. In many settings today, this need to move is satisfied in one of two ways: a child is given an opportunity to run around, climb things and generally engage with others in wild, unstructured physical play; or a child participate in organized sports, from soccer to dance to swimming, where his movements are coordinated around the rules of the game and often directed by adults.

These are valuable experiences, but a Montessori environment offers a child the opportunity to engage in a different, third type of movement: concentrated, self-initiated movement.

As Montessori educators, we recognize that children have an innate, almost instinctive need to engage in purposeful, mind-guided action, and we know that this need manifests itself in concentrated activity. Through concentrated work, children utilize muscles through activities that draw them, they repeat the same task over the over to master their own body, and they build simpler acts (such as pouring) into increasingly complex logical sequences (such as washing a table).

Purposeful, deliberate movement is at the core of the Montessori approach to early childhood education. While you will not see children run, climb on furniture, or throw materials around in our Montessori classrooms, if you watch closely, you will see coordinated movement everywhere:

- A two-year-old may be getting the table ready for a meal. He’s teaming up with a friend to carry one little table and place it right next to another, so several companions can enjoy a meal together. Next, he carries little chairs and places them by the table, then puts placemats or a tablecloth on it. He retrieves, one-by-one, small, real china plates from a nearby shelf; he carefully carries them with both hands, and places them with a graceful, controlled motion onto the table. He adds forks, spoons, napkins, glasses: this process may well occupy him for the better part of half an hour, and it involves numerous voluntary motor movements,

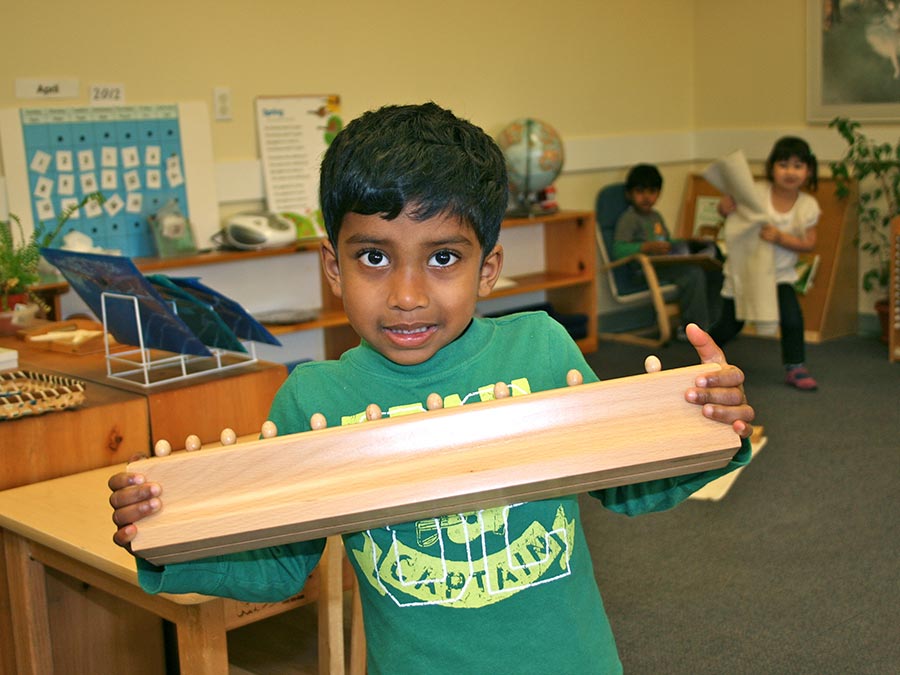

all of which are purposeful and deeply satisfying to the child! - A three-year-old may be carrying a heavy wooden block with inset cylinders from a shelf to a table. He’s straining his upper body muscles to heft this huge object; he’s exercising control over his arm muscles as he carefully holds it level lest the cylinders crash down on the floor. He controls the speed of his movement as he sets it down on the table, trying to do so without a sound. All that, before he has even begun the work of removing the knobbed cylinders and replacing them with a three-finger grip!

- A four-year-old may be walking on an oval line on the classroom floor, carefully putting one foot right in front of the next as he exercises his sense of balance, and learns to purposefully slow down. He may challenge himself further by carrying a glass full of water, or balancing a pillow on his head, or by moving his feet in rhythm with the quiet music playing in the background.

- A five-year-old is working on grammar. The teacher, sitting in a corner of the room, hands her a little slip, on which is written "the spotted cow." The girl reads this, then carefully walks to the Little Farm on the other side of the room, and picks out a figure of a spotted cow. She carries it, controlling her urge to run with her find as she walks around the mats where her friends work, around the shelves with the materials, and puts the little figure back on her table. She then carefully picks out grammar symbols identifying the article, adjective, and noun, and places them above the words on the slip of paper.

When children live daily in a Montessori classroom, they learn through activity to coordinate their muscles and place them under the ready control of their mind. The joy they experience in this purposeful movement is akin to the motivation we as adults feel when we master a new sport, an instrument, or any other purposeful physical feat. In Montessori’s words:

The external aim [of the activity] was only a stimulus. The real aim was to satisfy an unconscious need, and this is why the operation is formative, for the child’s repetition was laying down in his nervous system an entirely new system of controls, in other words, establishing fresh co-ordinations between his muscles, co-ordinations not given by nature, but having to be acquired. It happens no differently with ourselves in sport, in all games that we repeat with enthusiasm. Tennis, football, and the like, do not have for their sole purpose the accurate moving of the ball, but they challenge us to acquire a new skill–something lacking before–and this feeling of enhancing our abilities is the real core of our delight in the game. (The Absorbent Mind, p. 180)

Many teachers in elementary schools have noticed that children come to them unable to control their bodies. They lack the dexterity to hold a pencil properly to write. They bump into furniture and each other as they move about the room. They cannot control their muscles well enough to tie shoe laces, or to replace food in their lunch boxes without making a mess, or use utensils properly to eat. Often, they have not learned to control their bodies well enough to hold themselves still in situations that call for stillness. .

While children grow in height automatically as they age, they do not grow in motor skills the same way. Without proper motives for activity, such as those found in a Montessori environment, children may miss the sensitive period in which coordinated movement develops optimally. Instead of channeling their childhood urge to move towards concentrated activity that helps them to gain control over their own bodies, they may expend much exuberant, plentiful energy in less purposeful movements, which do not yield the same benefit of coordination, refinement, and intellectual as well as muscular growth (and which as a result are not even as emotionally satisfying to a child).

As Dr. Montessori so wonderfully put it:

To give them their right place, man’s movements must be coordinated with the center–with the brain. Not only are thought and action two parts of the same occurrence, but it is through movement that the higher life expresses itself. To suppose otherwise is to make of man’s body a mass of muscles without a brain. (The Absorbent Mind, p. 141)

So when we look at an active, rambunctious 3-year-old running into our classroom on the first day of school, we do not see a misadjusted or hyperactive child. We see a child at the cusp of a sensitive period for movement, a child whose mind and body are calling for an opportunity to concentrate, a child who, in a carefully prepared environment full of enticing stimuli, will bring his abundant physical energy under the control of his will. We are excited to welcome him into our midst, and to experience together with you, his parents, the wonderful journey of growth as this little person learns to master his body to manifest his own unique personality.